Bibliography

Falckenberg, H. Weibel, J (2009). Paul Thek: The Artist's Artist. Massachussets: MIT Press

Friedberg, A (2006). The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Massachusetts: MIT Press

Derrida, J (2005). On Touching - Jean-Luc Nancy. Stanford University Press

Dent, P (2020). Sculpture and Touch. Routledge Press

Flusser, V (2000) Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Reaktion Books

Perella, C (2007) Ian Kiaer: British School at Rome. British Council

Schwenger, P (2006) The Tears of Things: Melancholy and Physical Objects. University of Minnesota Press.

Brubaker, D (2003) Merleau-Ponty’s Eye and Mind: Rethinking the Visible. Journal of Contemporary Thought, 17 ed.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1948). The World of Perception. Reprint, Oxford: Routledge, 2004

Pelzer-Montada, R. (2008) The Attraction of Print: Notes on the Surface of the (Art) Print, Art Journal, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 74-91.

Falckenberg, H. Weibel, J (2009). Paul Thek: The Artist's Artist. Massachussets: MIT Press

https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/274532/what-was-the-original-usage-of-the-term-haptic (Accessed 17/05/2025)

Perez-Oramas, (2018) https://post.moma.org/part-1-lygia-clark-if-you-hold-a-stone/ Lygia Clark (Accessed 19/05/2025)

https://iep.utm.edu/husspemb/ Husserl (Accessed 27/04/2025)

https://lindsayseers.info/work/320/ (Accessed 17/05/2025)

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/results/r?_q=millbank+penitentiary&_sd=&_ed=&_hb= (Accessed 20/04/2025)

https://alondoninheritance.com/london-buildings/millbank-estate-millbank-penitentiary/ (Accessed 20/04/2025)

https://www.vivianesassen.com/works/of-mud-and-lotus/ (Accessed 28/04/2025)

https://siennapatti.com/artist/bettina-speckner (Accessed 02/05/2025)

https://www.whitecube.com/artists/danh-vo (Accessed 02/05/2025)

https://paulcoldwell.org/portfolio-item/prints-2019/ (Accessed 17/05/2025)

https://www.rachaelcauser.com/ (Accessed 19/05/2025)

https://m2gallery.com/ (Accessed 19/05/2025)

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG175547 (Accessed 20/05/2025)

https://www.polkagalerie.com/en/miho-kajioka-works-and-where-did-the-peacocks-go.htm (Accessed 20/05/2025)

https://www.tate.org.uk/research/in-focus/heroic-symbols-anselm-kiefer/difficult-reception-occupations (Accessed 20/05/2025)

Rachael Causer:Talk and Exhibition at M2 Gallery

Rachael Causer is London-based artist who creates sculptures which elevate, animate and re-frame traces of the everyday. She talked to us about her practice from the point of graduating in 2020 from the MA Printmaking course, to her current work and her exhibition Thatch at M2 Gallery in Peckham.

I identify with Causer's sensitivity to material and her playful process of making, which she described in her talk as 'physical encounters with the world'. Causer often uses plaster, sometimes tinted with a pastel hue, from which she casts surfaces and cavities of objects which are often domestic, everyday, and from the 'non-art' world. About the work Notch, she describes the process of casting the edge of a carpet, an 'overlooked' surface-object, and the act of pulling away the plaster to capture the carpet's form and texture along with its fibres and dust. Causer displays the work vertically and it becomes a new kind of edge, a dermis or gum, or a landscape to be traversed through touch... upwards?

Notch, 2023

The exhibition opening at M2 Gallery presents new works which Causer created specifically for the unusual space. Named the Gallery Pavilion, the space itself is a structure resembling a high-end architectural shed, in which works are displayed behind windows on each of its 4 walls. In her talk, Causer explained how she was able to remove the inner walls so that works could co-exist within the same space. She explained that she didnt know how the works would be arranged until she installed them, which chimed with my practice of playful arranging. The artist Ian Kaier, who works in a similar way writes: ‘I want to approach work always with an openness to the possibility of adjustment, though due to the necessity of actually presenting the work, at some point it does become fixed.’

This is hugely pertinent as I approach the Summer Exhibition with concern about balancing this sense of playful creation with the fixed nature of display. This is also important when I consider how I want the audience to view the work, and again I find recognition in Causer's intuitive approach to making and her statement 'I enjoy operating in the slippery ground between knowing and not knowing what something is'. Causer's works exist in the glass structure like creatures co-existing, independently and yet 'talking to one another'. Kiaer writes about the importance of the fragment in his work, trusting that the audience will naturally make associations between works that are juxtaposed. He also uses the phrase 'material gesture', which I love in relation to my work, and which certainly is true of the way we respond to Causer's exhibition.

.

Tenterhooks. Wood, blanket, steel, acrylic paint, 50 x 40 x 80cm. 2025

Thatch. Installation view. 2025

In her gallery talk, Causer reveals some of the questions she asked herself during the making process for Thatch. About the cast pipe inners, she asked: How do I raise, elevate or frame the work? How do I animate it? She describes the decision to make the stands or 'feet' for the works as a way to elevate and use display methods to give the work physicality. Tenterhooks was originally a display for another work, she relates, stating that sometimes the display mechanism is more interesting. The way Causer speaks about objects having 'potential uses', or 'different modes of being' I find particularly inspiring, as I often re-use objects and imagery in an attempt to drive more from something, to discover its various 'modes of being'.

Visit to British Museum Prints and Drawing Collection

I sent an email to the Prints and Drawings collection requesting a group visit for myself and two of my coursemates, along with a list of works we each wanted to view. Locating works on the British Museum catalogue was a task in itself, but I was lucky to find that one of my favourite Japanese woodcut artists, Ansei Uchima had 5 of his prints in the Asia Department collection. The others chose a range of works, including the original Dürer Rhinoceros drawing from 1515, a Turner print and a Constable drawing. I learnt a lot by compiling our list of works, not only about the different departments of the museum, but also about the rigorous process of recording and preserving items.

I'm fascinated by museums and the instinct the preserve and store. Years ago, after a visit to the Wellcome Museum and seeing the tattooed skin on display, I imagined someone proselytizing in the streets about the unnatural, irreligious practices of museums in preserving specimens, a way to question this culture of preservation which some might deem 'unnatural', 'ungodly'. I wrote a poem at the time (2012?) called Skin which was inspired by this thought.

Skin

When mother tells me I need to sleep

I tell her about the skin.

I tell her the worst of it is human,

Hard as shaved hoof and cooked with age –

Documents, so they are kept and called,

Ordered in drawers between desiccating beads,

Are etched with cartoon whores

Who lay down and perhaps loved, once

These sailors and criminals

Now grafted in part that they are to the air,

Quiet as a felted eardrum.

There, a sterile room about town’s

Used to keep the air around objects dry.

Feathers, crisply static as the day they fell,

And the one seed clean unstuck from its glass.

Too dry to stick, say the druggists.

Their old methods of packing their pills amongst rice

Near overthrown, they moisten their lips.

I should have known, as grain upon grain

Heap in the vertices of matchboxes

Tipped at the corner, and fall into wastepaper bins.

A selection of the works we viewed in the collection: (from left to right) pencil drawing by John Constable; mezzotint and etching by J.M.W Turner; etching by Samuel Palmer; pen and ink drawing by Albrecht Dürer)

Japanese woodcut print by Ansei Uchima

Temple Garden (artist's proof). Japanese woodcut print by Ansei Uchima. 1964

Close-up views of Temple Garden

Seeing Temple Garden 'in the flesh' and in this kind of studious setting was wonderful, as I had the time to really look at the technicalities of the print; from the cut line, to the bokashi (blend) and the layering. I'm also very inspired by the composition of this print; how it remains light and impressionistic yet graphic with its block forms. Uchima's prints may involve as many as 45 layers of colour in subtle tones. I currently work in a very controlled way when I compose my prints; tracing tones from a photograph from light to dark, only creating more abstract images because it's impossible for me not to simplify forms, partly because of the medium, but also because I am relatively inexperienced.

Ansei Uchima was born in the USA, but returned to Japan during the war years to study architecture at Waseda University. Following a chance encounter with the artist Onchi Koshiro, Uchima became interested in the Sosaku-hanga movement, in which printmakers turned away from the traditional format, themes and division of labour in the print studio, to working as printmaker-artists in their own right, whilst being influenced by Western Art, particularly abstraction.

Ansei Uchima, Fishing Lights, Japanese woodcut print, 1963

Ansei Uchima, Wind and Butterfly, Japanese woodcut print, 1959

I see Japanese woodcut as a practice I will continue to do as part of and alongside my practice as career, well into the future. I find it incredibly challenging and unpredictable, and, although I am able to do it at home without a press, it is not inexpensive. However, there is something about the quality of the process and the results (when they are successful) which really convey something important for me. There is something in the lightness of materials, the transparency of the paper and the ink, the layering of colour which really excites me. In studying Uchima's prints, I can see that I need (and want) to both improve my skill and loosen up my composition. I will continue to use photographs to build forms, but I will experiment with what Uchima termed 'weaving colour planes' to create more dynamic compositions. As I embark on a large-scale woodcut print for my Summer Exhibition, I feel lucky to have had this opportunity to reflect on my practice.

Artist Books: National Art Library and Anselm Kiefer at The Ashmolean Museum

I had two inspiring research visits which involved artist books: requesting and viewing artist books in the National Art Library at the V&A Museum, and coming across two of Anselm Kiefer's early photobooks at the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Early Works. As I consider where to take my work for the Research Festival, I have been considering the option of making a book; perhaps not an ordinary book, but a piece of work that is more sculptural in form, but which presents as a book.

The work which had to be carefully untied by the National Art Librarian, because it was such a hand-crafted object, was a book of digital prints and text by the Japanese photographer Miho Kajioka entitled And, Where Did the Peacocks Go? Kajoika's book was inspired by an anecdote she read about following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, which described peacocks being abandoned in the evacuation zone after the event. She reflects: “The image I had in my mind seemed so far away from what was going on in Fukushima,” Kajioka states. “It was as if two different layers of images – the disaster scene and beautiful peacocks – were overlapping with each other without being unified.”

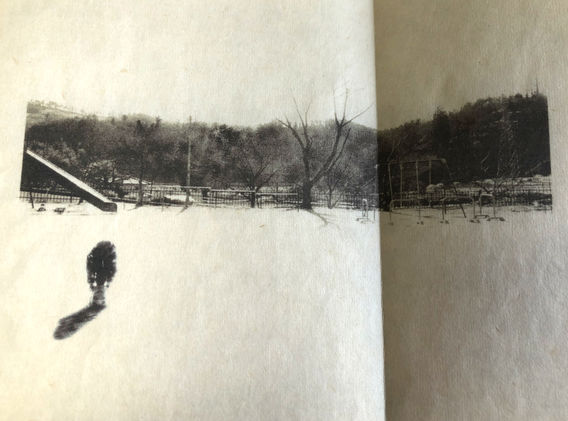

Miho Kajioka, And, Where Did the Peacocks Go? 2018

Miho Kajioka, And, Where Did the Peacocks Go? 2018

Kajioka is a photographer who works with intimately framed silver gelatin prints often depicting scenes of quietude, like scenes from a forgotten time. Her book includes even sparser versions of these photographs, which appear almost burnt into the Japanese paper and are often small sketched details within negative space. The text is hidden beneath the folded pages, and often reads like a memory or disparate thought.

Miho Kajioka, And, Where Did the Peacocks Go? 2018

The exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Early Works at the Ashmolean Museum is fascinating insight into Kiefer's early political works, including his Occupations photographs which he created in 1969 as an art student in Germany, in which he staged photographs of himself gesturing the Nazi salute. As part of the denazification of Germany, any such Nazi symbol or gesture had been banned, and so Kiefer's photographs form one of the first generation of post-war artists in the country to directly confront its history. The original photographs are juxtaposed with watercolours, hand-written annotations and hair in an intriguing collage of works which I find exciting in their fragmentedness.

Anselm Kiefer, Für Jean Genet, bound watercolour on paper, graphite, original photographs, hair and canvas strips on cardboard. 1969

There was also a huge, solid book with mounted woodcuts; 66 of them in total, depicting portraits of historical figures and abstract prints looking to have been printed directly from wooden planks. The physicality of this book is immense, a really sculptural construction.

Anselm Kiefer, Ways of Worldly Wisdom: Gottfried Keller. Woodcuts on Japanese paper mounted on cardboard and bound with canvas strips. 1977

The book-work which I found to be the most powerful is titled Burning of the Rural District of Buchen. It documents an imagined burning and destruction to the area of Buchen where Kiefer was living and working at the time. The page shown is one of the later pages of the book which are burnt and encrusted with charcoal, which, when combined with the photographs make for a beautiful but haunting materiality.

Anselm Kiefer, Burning of the Rural District of Buchen. Bound original photographs, ferric oxide and linseed oil on woodchip paper, 1974

I have included both the Kajioka photobook and Kiefer's book works because I feel that both have a power, but in very different conceptual and material ways. I have created two 'books' so far on the Masters course; my photobook bound in pewter and my handmade paper and hair book which resembles skin. As I continue to find ways to make prints more sculptural, I will consider using methods of binding, layering and mounting, as well as the juxtaposition of imagery the book provides.